Patrick Fransen

25 novembre 2014

SUSTAINABLE AND AFFORDABLE HOUSING

MODULO III: HOUSING AND INTERIOR DESIGN

Objective of workshop

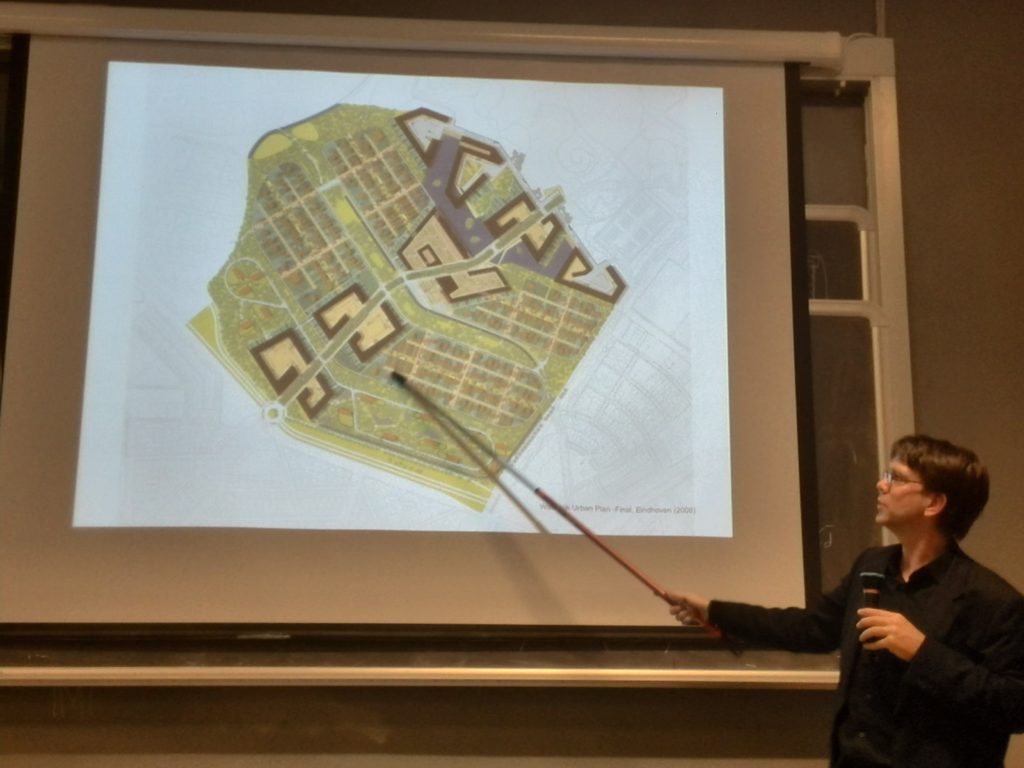

The existence and persistence of phenomena of social and environmental deterioration in our cities, of voids that lack any quality, of underutilized “zoned” areas, all seem to be passively accepted by local municipal administrations, as the inevitable consequences of the onslaught of building development that has devastated regional landscapes from the Second World-War onwards into the 1980’s.

researching grouping individual houses designed as one collective (house), positioned in a central courtyard of an urban block or any other void space in our cities, focussing on the relationship between existing and new houses also as on the social aspect of living together more than on the individual aspect of each individual needs. This might influence the urban tissue and the way we design our houses.

Course syllabus

Housing and social space

Only half a century ago many people in Western Europe lived in miserable conditions; the past is not far away but already forgotten. At this moment too much is focussed on the individual needs rather than on social aspects of living together.

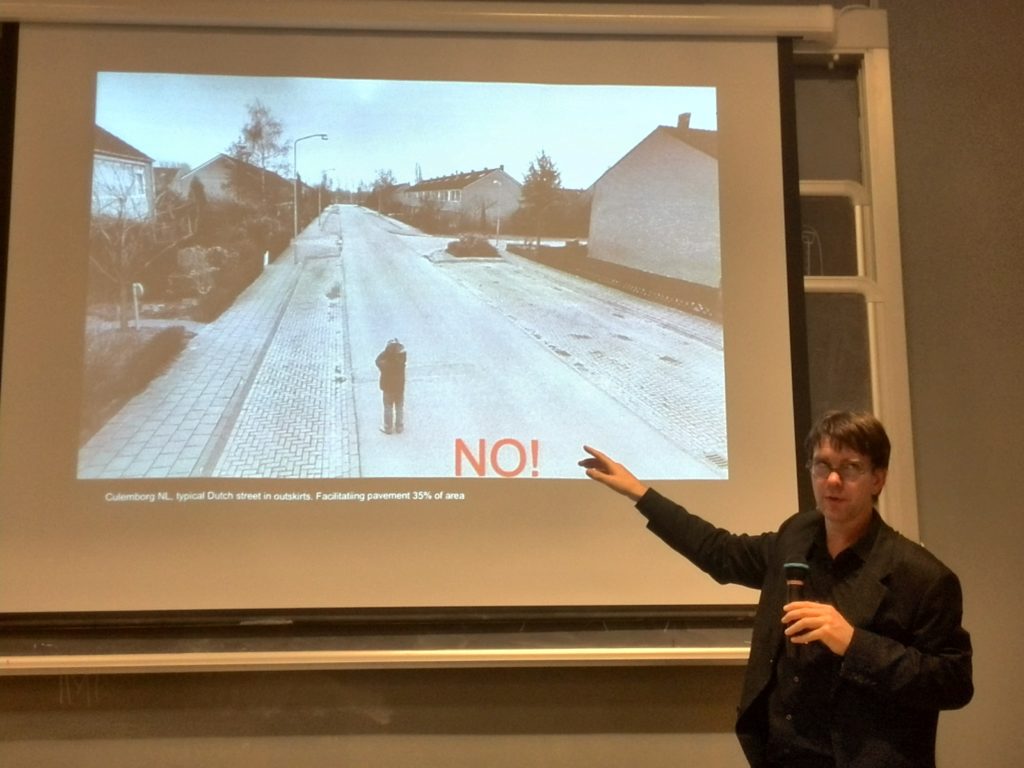

The cities often consisted of dirty streets with open sewers. They were subjected to polluted water supplies, insufficient open spaces and large areas of squalid housing and suffered from congested circulation. The countless workers – often sons of farmers from the countryside – were faced with a shortage of cheap housing. They came to work in the new industries. The city centres of major cities quickly became overcrowded. Due to a large natural increase in the second half of the 19th century, the cities faced a housing shortage. If we want to define the living conditions accurately we should not only look at the quality of the houses themselves but also at the quality of urban design. The reduction of high density does necessarily imply a better and healthier city. Equally as important is the social bond that people have with the street, the neighbourhood and the city. It is this bond and the associated sense of responsibility concerning the immediate exterior together with a good construction quality that determines the housing conditions.

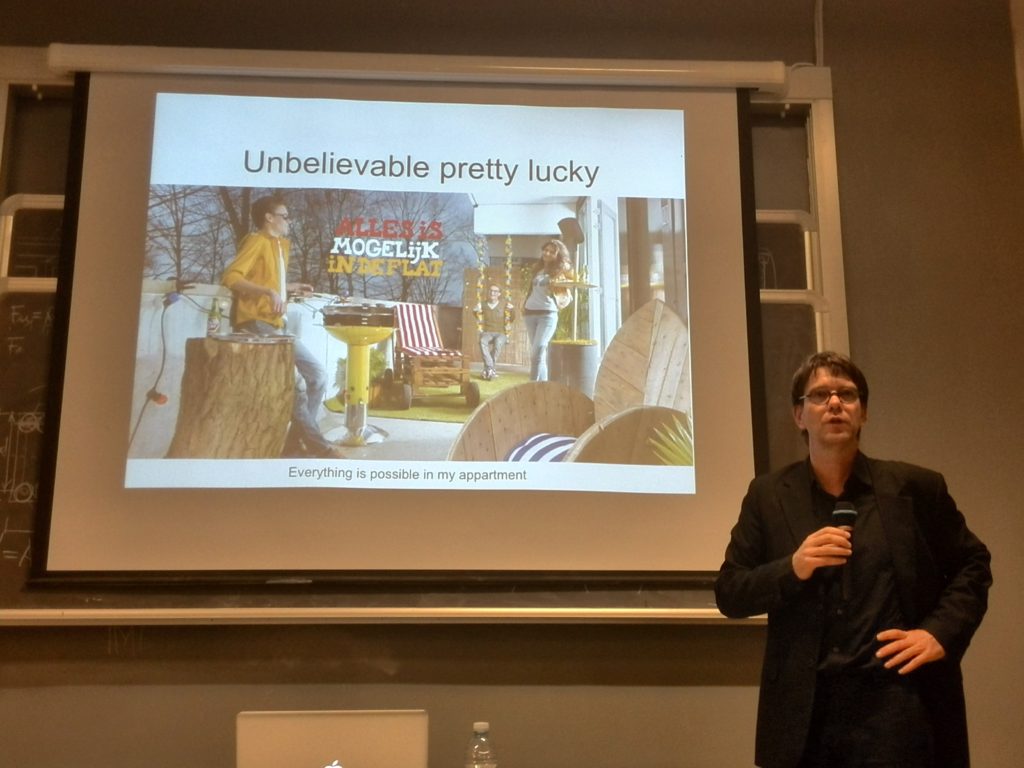

Cholera and typhus and other nasty diseases were still quite common in the first half of 20th century. Accordingly, Le Corbusier came up with a rigorous proposal for the centre of Paris: a garden-city, “Le Plan Voisin”. Although not conducted, there was a very large scale poor quality imitation of these plans in the sixties and seventies in the Western European suburbs. They were powered by an advanced industrialization and, again, a housing shortage, partly as a result of immigration to further rural depopulation. The park-like quality of the large-scale housing developments has been greatly reduced with the advent of the car. These are precisely the areas where there has been so much social turmoil. They are anonymous residential areas where the immigrant and native residents often do not understand each other. These urban structures have not anticipated social and environmental contexts.

Luckiliy good examples still exist. The main quality lies in the intermediate collective gardens, public spaces and sports facilities. The best known examples are the HBM by Henri Sauvage in Paris and Tony Garnier in Lyon based on garden-city ideas of Ebenezer Howard. “Siedlung Halen” (Bern, Atelier 5) is one of the best examples of modern social housing in Europe. Virtually a flattened Unité, clearly demonstrating the advantages of streets without traffic, creating social space. Nowadays social housing is becoming again more and more an emerging topic. Do not misunderstand it with housing for the poor. In my opinion it stands for affordable housing with more attention to the social aspect of living together, rather than focusiing on each individual needs.